The returned Canada geese are looking to make nests, with the ganders marching about protectively, but they are not impressed with having to arrive on ice. They exhibit an interesting landing maneuver coming in feet first and then getting around like an icebreaker. They do look well-fattened from where ever they are coming from. The birds may be a pest in places, but they belong here, and their honking arrival is delightful. The geese's spirit is harbinger of new life and summer around the corner. Thank God, he made such large and sturdy, sometimes comical, birds for our climate.

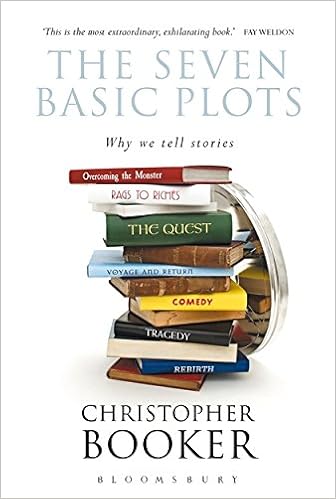

Meanwhile, I had taken the opportunity to read some huge "honking" books. One was "Seven Basic Plots. Why we tell stories." The author is Christopher Booker. 736 pages.

For some time, I wanted to explore the topic of "plots" because story telling does not come to me naturally as a passion or art form. Well, not since about grade 5 or so, when we started learning foreign languages in school and explored other "real" countries and histories in books or through actual travel, as is easily afforded living in Europe. Before that we made up plays from props in the house or used our puppet theater. I enjoyed Mr. Booker's book because he broke down the plotting not so much in a dry, technical way but in terms of what is going on with the characters, and that in a sort of archetypal way, making the application universal. The critics of his book would say that he has put a kind of straight-jacket onto story-telling, discarding all those stories that don't fit the schemes, especially more modern ones, as somehow deficient. It may seem that Booker would say that story-telling has devolved in some respects.

It really is a tome to reckon with. Many stories are explored in great detail, resulting in my feeling better equipped to tailor future reading after his analysis. Someone asked me if I felt more ready to write a story after reading this book, and I have to say that I don't think so. My passion is always to find out what is really going on in a past or current situation, and the idea of storytelling gives me the feeling of artificiality and manipulation. Someone told me: "Push through to untruth". -- I don't know. I want to know how it is EXACTLY. Does that need to be overcome to be an effective storyteller? Jesus was a storyteller, but his stories were obvious parables. Everyone understood that they were brief analogies. But in a sense Jesus' stories were "manipulation" as he broke the news to people in unexpected ways, having them let down their guard to listen with interest.

Sometimes, though, people leaning to the fiction side of storytelling can't tell the difference anymore between truth and untruth. So I find that also Booker won't distinguish between the fanciful and the real, at times. For example, he discusses the use of the unexpected, miraculous weapon that will defeat the enemy. Here he basically puts side by side James Bond and King David. James Bond always has a new weapon or vehicle up his sleeve to extricate him from dire circumstances to save himself, the girl and the world. We seriously get a comparison here from the esteemed Mr. Booker to the ancient King David who killed the giant with a stone and a sling-shot, receiving King Saul's daughter's hand in marriage. The only difference with the Bible stories are that they go on and on in time and don't have a properly resolved ending. --Yes, really.

There problem, as I see it, with this is that the literary giants of our times and other times don't believe that Bible stories are "real" stories, that is true stories, in the way that the non-literary person conceives a "true story". We are to see everything under out eyes in an archetypally true way ONLY. If you don't agree, you are a Philistine to them (in the non-literal way, of course, as if there had never ever really been any Philistines.)

So much for Booker's book. It is exhaustive and I believe he spent a lifetime, over 30 years, slaying the giant of getting everything under control neatly, even David and Goliath.

The other very large book I enjoyed was George Elliot's "Middlemarch". It is, of course, a famous novel, written by a woman who needs no introduction. The volume had sat on my shelf ever since I purchased it in a used bookstore under some mysterious prompting. It revealed itself to me, just now, and I really, really loved it. Seriously, I am a fan, all 900 pages of it. It is superfluous to tell you why it was wonderful, as it such a dearly loved classic. But I will just say that the novel served to illustrate some of Christopher Booker's points about characters and the arcs of stories. In Dorothea we have a typical lovely female serving as the great prize that needs to wrestled away from the dragon of upper-class snobbery by the unlikely hero in the form of the honorable but unconventional Ladislaw. Ladislaw is in effect a writer disguised as a dilettante. We could say that we have again a book written by a writer about a writers.

In Middlemarch, we find another kind of author, the famous Rev. Edward Casaubon, muddled and mired very deeply in his endless research. Ironically, he vaguely reminds me of the just before-mentioned Mr. Booker, in trying to systematize and unite all types of stories. Casaubon labored his entire life in the libraries hoping to produce his grand book of "The Key to all Mythologies." Like Mr. Booker he may have been overreaching, but nevertheless, we should sympathize with him in his great effort and its attendant result, his early death, as articulated and forever noted, by the great philosopher Solomon (of actual existence): "Of making many books there is no end, and much study wearies the body." (Ecclesiastes 12:12)

No comments:

Post a Comment